We often work with various datasets ranging from healthcare and tourism to finance. As technical experts, we excel at analyzing them, building sophisticated models, and crafting visually appealing dashboards. Yet, one skill we often overlook is communicating these insights to people who don’t share our domain expertise.

There are several ways to communicate data1:

- Data Reporting: These are the classic dashboards in which we present the data in an orderly way but leave the burden of interpreting it to the reader.

- Data Presentation: We present data in an organized way through an orderly speech. This is the classic slide presentation in which we explain the results of our analysis step by step.

- Data Storytelling: We build a narrative around the data and exploit the power of stories to engage the audience on an emotional and behavioral level.

This post focuses on data storytelling, combining data, visualizations, and narratives2. The literature debates data storytelling. Some consider it a narrative that supports the data, while others think it is data that supports a narrative3. In this post, we assume that the narrative we will build is firmly anchored to data and that we talk about data storytelling only when the story we make starts from data.

To build a data-driven story, we must use a basic narrative model. Various models exist in the literature, such as the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) pyramid4, or other models taken from cinema5,6,1. Here, we focus on the three-act structure taken from cinema1.

In the world of cinema and novels, every story is about a hero wanting something, but a problem prevents them from reaching it. A story can be organized into three acts: the first presents the hero and their object of desire, the second focuses on the problem, and the third explains if the hero solves the problem and reaches the object of desire.

The three-act structure, commonly used in screenwriting and novels, can be repurposed as a cognitive model for organizing a data-driven story:

- Act I – Setup: Introduce the context, the domain, and the data hero, such as a central metric, trend, or entity representing the story’s focal point.

- Act II – Confrontation: Present the problem from the data. This could be a deviation from expected performance, an anomaly, a bias, or a systemic challenge uncovered through analysis.

- Act III – Resolution: Offer conclusions, implications, or recommended actions. Whether the outcome is a resolved issue or an open challenge, the story reaches a narrative climax, often tied to a decision point or strategic inflection.

This structure does more than organize content. It mirrors how humans process information through temporal arcs, contrast, and transformation. Rather than listing metrics or showing dashboards without context, the three-act structure offers a logical and emotional progression that starts with instinct reaction, moves to emotions, and finally influences behavior (see the Stomach-Heart-Brain theory in Lo Duca1).

The three-act structure can be applied in many contexts for computing professionals, not only to data storytelling. For example, it can communicate system performance degradation, present A/B test results, and explain fairness concerns in machine learning models. In each case, a structured, story-driven narrative is often the difference between being heard and being understood.

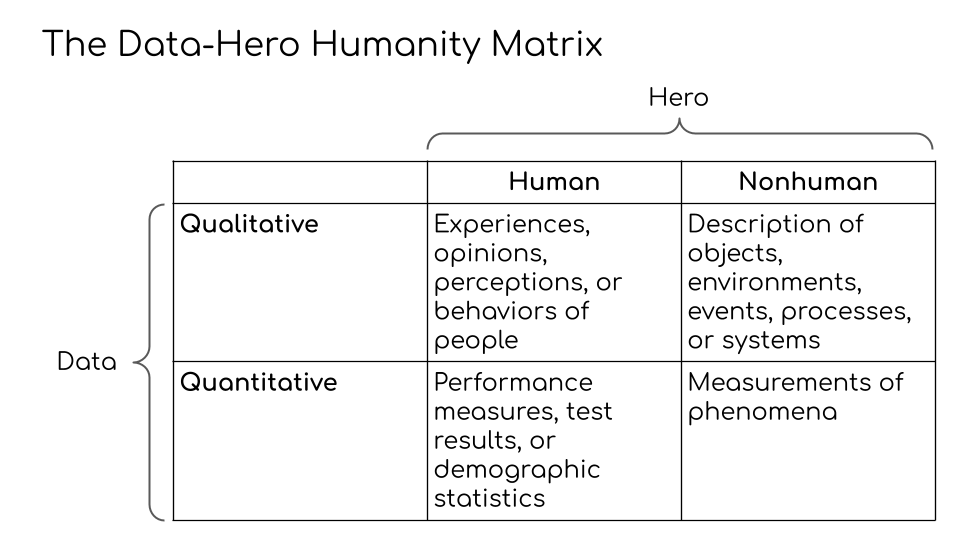

In traditional narratives, the hero is a story’s main character and drives it forward. In data storytelling, the hero is the data element that embodies the core issue, the variable whose trajectory reveals insight, risk, or opportunity. More specifically, the hero is a person, group, or entity represented in the data, someone who wants something but is facing a problem. Depending on your dataset, that hero can take many forms. To help identify them, I use the Data-Hero Humanity Matrix, which helps classify data subjects based on two axes: human vs. nonhuman, and qualitative vs. quantitative (Figure 1).

Based on the data type (qualitative or quantitative), we can extract the hero type (human or nonhuman).

Here are a few examples:

- Human + Qualitative:

Students sharing their learning experiences. Patients describing symptoms. Library visitors talking about their reading habits. - Human + Quantitative:

Demographic trends. Test scores. Performance metrics across populations. - Nonhuman + Quantitative:

Temperature readings. Product performance. Environmental metrics. - Nonhuman + Qualitative:

Descriptions of events, processes, or systems.

This human-centered reframing is not just rhetorical; it’s functional because it helps bridge the gap between analysts and decision-makers, between machine outputs and human interpretation. It ensures the story’s hero isn’t just a number, but a proxy for what’s at stake.

Data storytelling creates tension by clearly identifying what supports the hero (the sidekick) and what threatens them (the antagonist). These narrative roles help transform data from static reports into dynamic, decision-relevant narratives.

The sidekick brings human specificity to abstract metrics. In data storytelling, this often takes the form of:

- A representative user story, drawn from qualitative research or feedback.

- A case study illustrating the broader trend reflected in the data.

- A domain expert, offering context or interpretation.

For instance, in a story about decreasing engagement with an online learning platform (the hero), a real student interview (the sidekick) can illustrate why the numbers are dropping. This makes the data relatable, not just readable.

Every good story needs conflict, and so does every compelling dataset. The antagonist in a data story is the cause behind the problem preventing the hero from achieving its goal. This could be:

- A technical bottleneck (e.g., memory leaks affecting throughput).

- A behavioral trend (e.g., user drop-off after onboarding).

- A systemic issue (e.g., algorithmic bias, infrastructure fragility).

Identifying an antagonist forces us to go beyond correlation and toward causal insight. It also clarifies the stakes: What happens if the problem persists?

When we explicitly frame the narrative around these characters, hero, sidekick, and antagonist, we move from data presentation to data storytelling. We give audiences not only the facts. but a reason to care.

Let’s consider a straightforward case study: the rise in global temperatures. We start, as every good data story should, with the data. In this case, quantitative measurements track a long-term climate trend. Referring to the Data-Hero Humanity Matrix, we deal with a non-human, quantitative hero. Our hero, then, is the temperature itself. Its object of desire is simple and measurable: to remain stable over time. Yet, the data reveals a clear shift. Since 1977, average global temperatures have been rising steadily. This trend is the core problem in our story. Like any good story, a problem is rarely without a cause. The antagonist is human activity: Greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and unsustainable energy use all contribute to the temperature’s deviation from stability.

Once we’ve defined our narrative, we can structure it using the three-act structure:

- Act I – Setup: We introduce the temperature hero and optionally a sidekick, such as a climate scientist who helps interpret the data and brings a human perspective to the story.

- Act II – Confrontation: We present the problem. Visualizations show the increasing temperature anomalies, aligned with graphs of industrial emissions and other anthropogenic indicators.

- Act III – Resolution: We propose solutions to help our hero, such as actions that reduce emissions, promote sustainability, and mitigate future damage. The outcome isn’t guaranteed, but the path forward is visible.

This structure transforms data into a narrative with which audiences can engage emotionally and cognitively. By giving even abstract metrics a role in a story, we move from dashboards to decisions, from numbers to meaning.

Data storytelling is not about embellishment. It’s about effectiveness. As computing professionals, we already have analytical rigor and technical depth. What we often lack is narrative clarity: the ability to structure, contextualize, and deliver insights in a way that drives understanding and action.

Borrowing from cinematic storytelling is not a soft skill add-on; it’s a strategic communication practice. It enables us to craft narratives that make sense of complexity, clarify uncertainty, and connect data to decisions. How we tell the story of the data determines the impact we make.

Data storytelling is the differentiator in an age of dashboards, KPIs, and automated insights. It turns information into influence. The future of data science won’t be shaped only by better algorithms, but also by better data storytellers.

1. Lo Duca, A. (2025). Become a Great Data Storyteller. John Wiley & Sons.

2. Dykes, B. (2019). Effective Data Storytelling. John Wiley & Sons.

3. Dykes, B (2024) Data Stories vs. Stories With Data: What’s The Difference? Retrieved from https://www.effectivedatastorytelling.com/post/data-stories-vs-stories-with-data-whats-the-difference (Last Access 2025/04/14)

4. Lo Duca, A. and McDowell, K. (2024). Using the S-DIKW Framework to Transform Data Visualization into Data Storytelling. The Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST). DOI 10.1002/asi.24973

5. Wei, Z., Qu, H., & Xu, X. (2024). Telling Data Stories with the Hero’s Journey: Design Guidance for Creating Data Videos. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics.

6. Yang, L., Xu, X., Lan, X., Liu, Z., Guo, S., Shi, Y., Qu, H., and Cao, N. (2021). A design space for applying the freytag’s pyramid structure to data stories. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 28(1), 922-932.

Angelica Lo Duca is a researcher at the Institute of Informatics

and Telematics of the National Research Council, Italy. Her research interests include data storytelling and the application of AI to

different domains, including cultural heritage, tourism, education, and more. She is the author of Data Storytelling with Altair and AI (Manning Publications, 2024) and Become a Great Data Storyteller (Wiley, 2025).