What is the interior of a circle? Obvious.

What is the interior of a parabola? Not quite as obvious.

What is the interior of a hyperbola? Not at all obvious.

Is it possible to define interior in a way that applies to all conic sections?

Circles

If you remove a circle from the plane, there are two components left. Which one is the interior and which one is the exterior?

Obviously the bounded part is the interior and the unbounded part is the exterior. But using boundedness as our criteria runs into immediate problems.

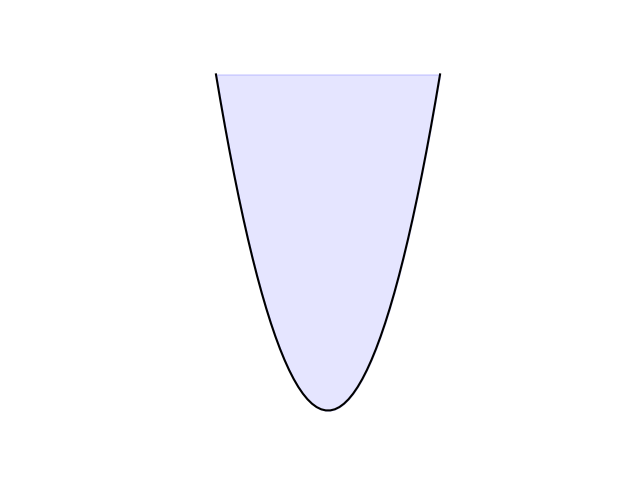

Parabolas

If you remove a parabola in the plane, which component is the interior and which is the exterior? You might say there is no interior because both components of the plane minus the parabola are unbounded. Still, if you had to label one of the components the interior, you’d probably say the smaller one.

But is the “smaller” component really smaller? Both components have infinite area. You could patch this up by taking a square centered at the origin and letting its size grow to infinity. The interior of the parabola is the component that has smaller area inside the square all along the way.

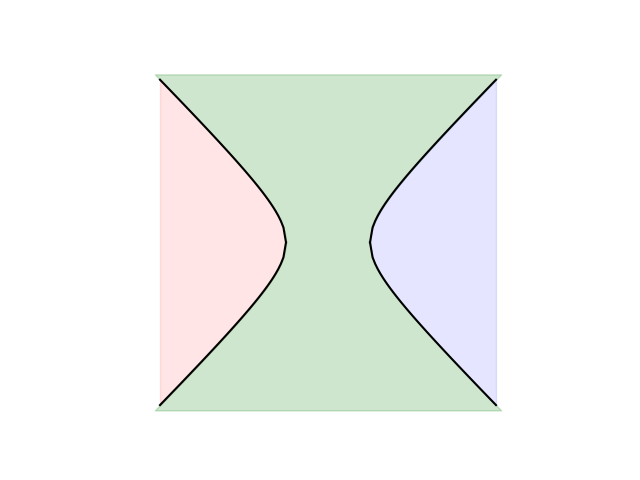

Hyperbolas

A hyperbola divides the plane into three regions. Which of these is the interior? If we try to look at area inside an expanding square, it’s not clear which component(s) will have more or less area. Seems like it may depend on the location of the center of the square relative to the position of the hyperbola.

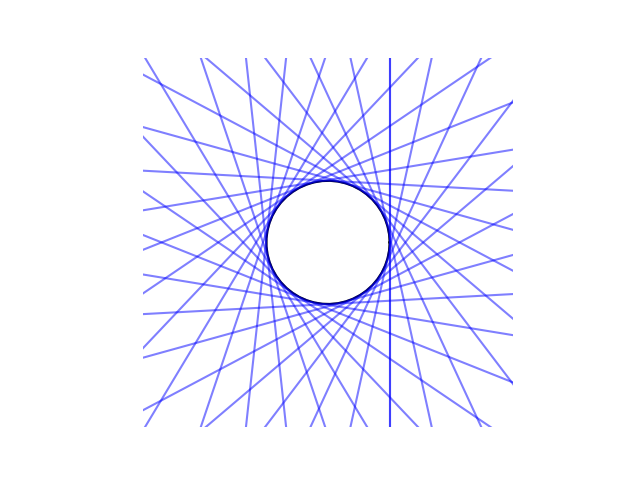

Tangents to a circle

Here’s another way to define the interior of a circle. Look at the set of all lines that are tangent to a point on the circle. None of them go through the interior of the circle. We can define the interior of the circle as the set of points that no tangent line passes through.

This clearly works for a circle, and it’s almost as clear that it would work for an ellipse.

How do we define the exterior of a circle? We could just say it’s the part of the plane that isn’t the interior or the circle itself. But there is a more interesting definition. If the interior of the circle consists of points that tangent lines don’t pass through, the exterior of the circle consists of the set of points that tangent lines do pass thorough. Twice in fact: every point outside the circle is at the intersection of two lines tangent to the circle.

To put it another way, consider the set of all tangent lines to a circle. Every point in the plane is part of zero, one, or two of these lines. The interior of the circle is the set of points that belong to zero tangent lines. The circle is the set of points that belong to one tangent line. The exterior of the circle is the set of points that belong to two tangent lines.

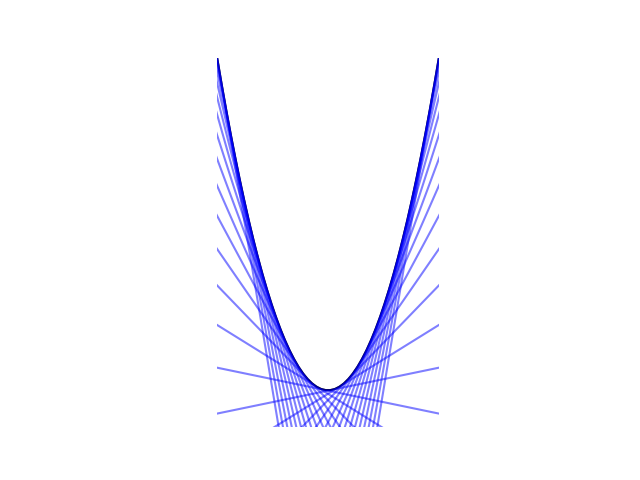

Tangents to a parabola

If we apply the analogous definition to a parabola, the interior of the parabola works out to be the part we’d like to call the interior.

It’s not obvious that every point of the plane not on the parabola and not in the interior lies at the intersection of two tangent lines, but it’s true.

Tangents to a hyperbola

If we look at the hyperbola x² − y² = 1 and draw tangent lines, the interior, the portion of the plane with no crossing tangent lines, is the union of two components, one containing (−∞, 1) and one containing (1, ∞). The exterior is then the component containing the line y = x. In the image above, the pink and lavender components are the interior and the green component is the exterior.

It’s unsatisfying that the interior of the hyperbola is disconnected. Also, I believe the exterior is missing the origin. Both of these annoyances go away when we add points at infinity. In the projective plane, the complement of a conic section consists of two connected components, the interior and the exterior.